On that cold, windy evening, with grey clouds threatening imminent rain, I raced the rotation of the earth up a steep path to a peak from which I hoped to observe the sun dip into the vast East China Sea off the coast of Jejudo; Jeju Island. As I labored forward, I heard from behind me the hurried footfall of a fellow hiker and turned in time to observe a man step through a gap in the fence, hoisting a bale of hay over one shoulder, a heavy bag on the other, and a large plastic bucket in hand. He continued down a treacherous narrow path, somewhat parallel to mine, to a grassy, flat area where he deposited his burdens. Intrigued, I used my curiosity as justification to catch my breath and watched to see what he was up to. He deftly cut and gathered small branches and dry grass together and ignited a fire which rose rapidly as he added heavier branches to increase the flame and warmth. The steady sea breeze fanned the flames and a lively campfire was quickly established. He grabbed a blanket from his bag and spread it out before him and then, slinging the bucket, he poured golden oats across it in a neat pile. From the bag, he pulled a metal and wood contraption and laid it before him. Separating several sections of hay from the bale, he placed them on the contraption which he used to chop the hay into small pieces which he added to the oats, stirring them together as he went. With the roaring fire behind him providing warmth and increasingly necessary light, he continued chopping hay and began whistling again and again, an invitation to dinner. Shortly, I spotted the arriving guests, two beautiful shaggy, white Jeju horses. Small in comparison to western breeds, they are a mix of the indigenous Jeju horse and the small Mongolian horse on which Genghis Kahn’s armies established conquest over most of the European and Asian continents. Despite the risk of missing the sunset, I continued to linger a bit to observe this lovely interaction which was so uniquely characteristic of life on Jejudo. The roaring campfire, hastily prepared meal, the spry horseman, and the shaggy horses, together on the steep cliffside in the relentless cold wind, high above the rocky shore and white capped waves below.

Alone in the vast China Sea off the Southern tip of the Korean Peninsula, Jejudo is Korea’s largest island. Centuries of tradition have evolved in a way which define Jejudo uniquely and its cultural traditions and beauty have made it such a popular destination that the air route between Seoul and Jejudo, with over 1,000,000 travelers annually, is purported to be the busiest in the world. A famous Korean proverb says; If a horse is born, it should go to Jejudo, a human born should go to Seoul. With the ease of air travel, human visitors from Seoul and the rest of the world now outnumber the horse by a considerable degree.

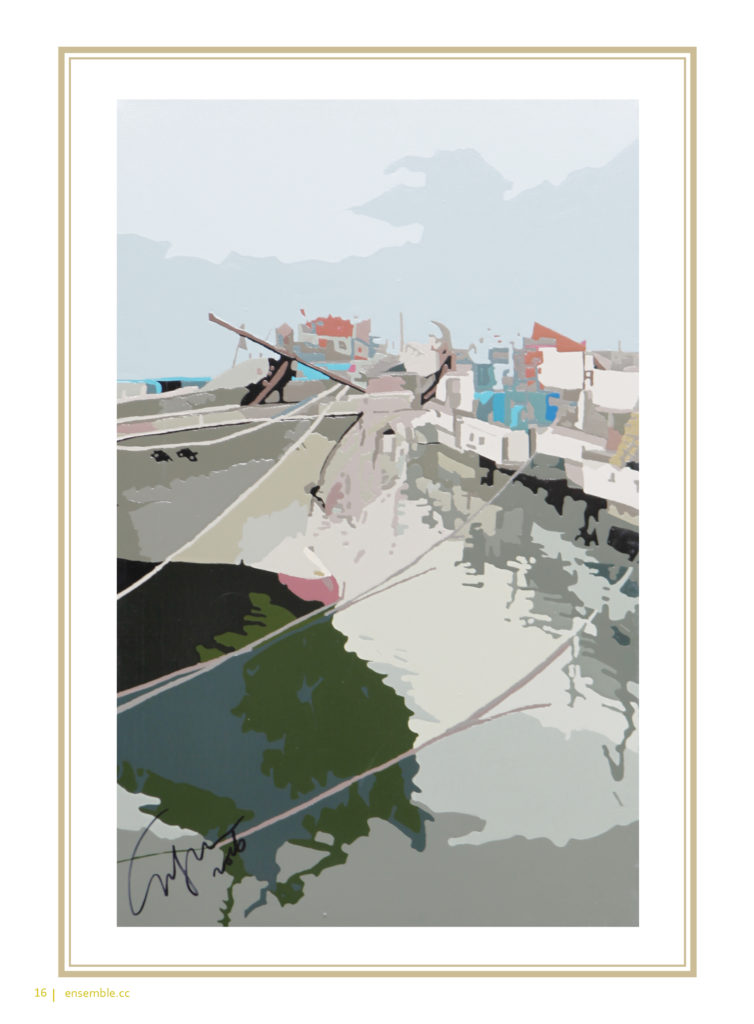

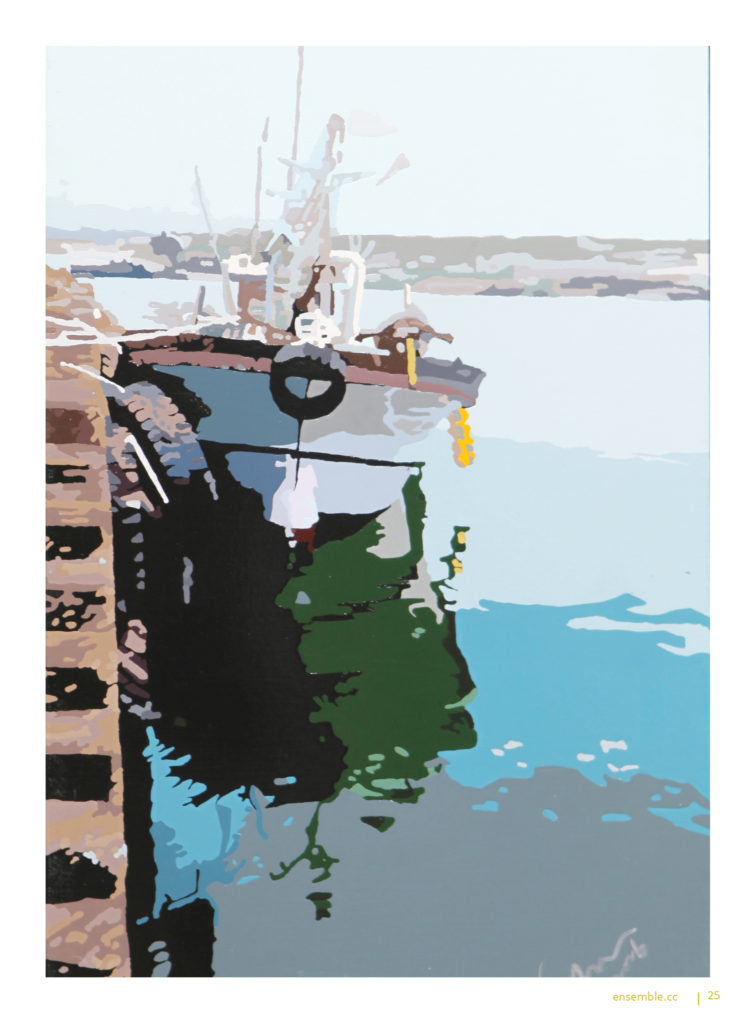

Like other islands of volcanic origin, it is characterized by tall mountains on the interior, fertile soil, and a rocky coast line. The ports along its circumference are full of all manner of water craft, the conveyances of the island’s fishing industry. Though tourism is a critical element of the island’s economy, fishing and agriculture have always been a mainstay of both economic and cultural character.

For most of the island’s history until the Joeson period, Jejudo developed in isolation with little contact or influence from the outside. It is said that the island is famous for three things evident; wind, stones, and strong women, and three things lacking; beggars, thieves, and locked gates. Its origin story refers to Seoulmundae Halmang (Grandmother Seoulmundae) who was so strong that she could step from one island to another in a single stride. She created Mount Halla by scooping earth in her hands, and had 500 children. The myth tells us that, while her children were away, she prepared a large kettle of soup for them but, falling into the kettle, she was drowned. Upon return, her children unwittingly drank the soup. Realizing later what had happened to their mother, they cried in misery until they were transformed into stones. Today, we see these stones as the ubiquitous dol hareubang (stone grandfather) sculptures and bangsatap, small, round towers made of many stones which ward off ill fortune. The ancient tradition of diving in the cold ocean waters for seafood which began as the task of brave men, gradually evolved into the exclusive profession of the island’s women. The famous Haenyeo (diving women) free dive in icy waters, remaining under water often over 2 minutes at a dive.

Today, the traditions of isolation and hearty self reliance are in frequent conflict with tourism and settlement by outsiders which bolster the economy but are perceived as threats to the traditional way of life for the indigenous community.

I have come here to witness the beauty and culture of Jejudo and to meet with one of its distinguished artists, Ms Kim Su Yeon. Ms. Kim earned her MFA at Jeju National University and is now entering her doctorate at Hongik University in Seoul. She has exhibited throughout Korea, Tianjin, China, New York City and Paris, receiving numerous awards along the way.

The day is cold and rainy, I have just visited Mr. Kim, Nam Heung one of the most recognized sculptors of dolhareubang as well as a variety of other wonderful stone works. We enjoyed tea beside a roaring fire after viewing his amazing work.

Now, at the studio of Su Yeon Kim, I have at last the opportunity to view and discuss her work. Ms. Kim’s family has lived on Jejudo for several centuries. The family home is in town, surrounded by tall new construction, an anachronism in its traditional architecture and warm atmosphere amidst the modern concrete structures. Ms. Kim’s studio is located in a dependent apartment beside the main family home. As I enter the apartment, I see a wonderful workspace in which a clever arrangement of living and work area are shared but every inch of discretional space is fully occupied by canvas and tools of the craft.

RCW: You refer to Memory in the title of these pieces. Tell me what you mean by that and how it is reflected in your work.

KSY: Memories are incomplete and imperfect. They float somewhere in our conscious and subconscious mind sometimes connected, sometimes disassociated and unconnected. Photographs act as a trigger to help reassemble the fractured memories. We assume that photographs represent the complete memory of events. However, if we recall the time when the photographs were taken, we may realize that our memories are not merely the images in the photograph but also all of the emotions and the associations and connections we experienced; from the time of the event to the moment when we view the images later. The art is not just the characters captured in the photographs. In other words, photographs as a tangible matter cannot be our memories. They are meaningful only as a means of assisting memories.

For me, photographs are a means of assisting the creative process. They provide the basic groundwork for drawing sketches and framework for coloring. In the process of sketching, a whole scene of a photograph is divided into pieces according to the effect of light and shade to express either segregation of imperfect memories or decayed memories. I use the medium of enamel because it has a similar texture to that of photographs. That is how I want to put together the segregated puzzle of memories.

We do not recall all memories of our life in their entirety. Memories are kept as broken pieces scattering here and there like a puzzle. Sometimes, scattered pieces of similar memories get together and give us a whole piece of memory. At other times, they are mixed together creating a new piece of memory. Accordingly, I convert the processes of segregation, reproduction, and creation of memories and divide them further through the process of object segregation by the effect of light and shade. My process intends to express objects in a simple color where each of the broken pieces has a uniform color determined by the degree of light and shade reflected in each piece, rather than showing the actual colors of the objects.

RCW: With some exception, your portfolio is predominately representations of the boats around Jejudo. How do we understand this focus in the context of your work statement?

KSY: You may be surprised to know that I have rarely been aboard a boat. I am inclined to motion sickness. In some way, I am moored to Jejudo. I experience the boats which go out to sea, disappearing beyond the horizon, returning to Jejudo, encountering each other at times, at times journeying alone, as individual characters, creatures like myself. We share a love of our homeland. I am their witness.

RCW: I would like to ask you about a few of your works. This first piece is of the sea from the side of the boat and we can see the glass lamps which are strung along the decks of the fishing boats here.

KSY: I created this piece at a time when I was depressed and tired. I was inclined to draw something simple and uncomplicated. When I painted the glass lamps, so clear and pure, the simplicity and brightness of the piece lifted me out of my gloomy feeling.

RCW: One of the things I appreciated about this piece is that this lamp is so characteristic of the boats I have seen in the harbor. They give the otherwise industrial appearance of the boat a kind of cheerfulness.

KSY: The lamps are carefully maintained by the fishermen to illuminate the water and help the men to catch the fish. When the lamp is polished and clean, it shines brightly and captures beautiful reflections. But as the lamps become dusty or damaged in use, their light is diminished and the special reflective qualities are lost. This reminds me of our human condition in some way.

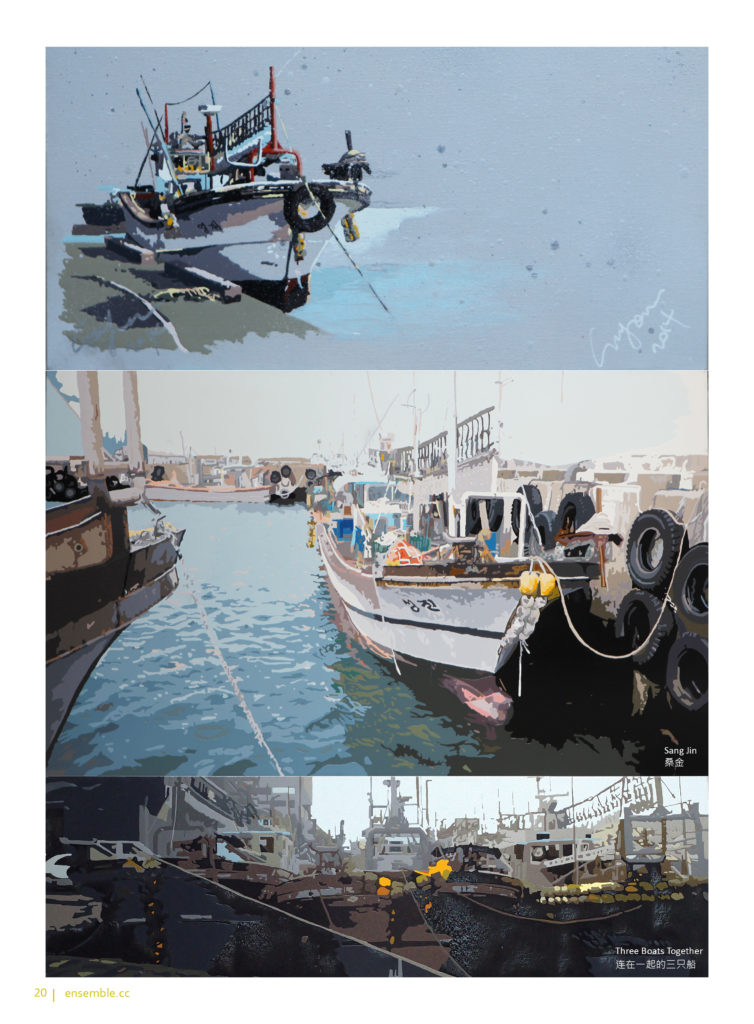

RCW: Next is this piece, a boat, named Sang Jin, tethered to the dock.

KSY: This piece is my graduation piece. Coincidentally, the boat’s name, Sang Jin, happens to be the name of my professor. My professor’s character was often cheerful and happy but also quickly changeable to demanding and fierce like a tiger. I often felt stressful in the tug and pull of my professor’s demands and the challenges and limitations of school itself. In this painting, there are tires attached to the dock. The boat is tethered to the dock by rope. The painting is a representation of my experiences striving as an artist. I am moved by the waves and tides of stress, challenge, inspiration, and emotion but tethered and constrained by circumstances, societal structure, outward and inward limitations. Like the boat, I want to be free to sail the waves of my inspiration but I endure the constraints of reality; at least for a time.

RCW: This next piece shows a series of boats tied to dock.

KSY: I often go to the harbor on the east side of Jejudo. Ships come and go from this harbor, not just to the fishing grounds but also to other countries, adventures far abroad. But these boats in the painting seem to be always be tied up together. Whenever I go to that harbor, I see these three boats together. I think of them as myself and my siblings. In the middle is me, the one of the left is my younger brother and the right side is my sister. They can travel wherever they choose, but they have a powerful connection, like the connection of family. The left side boat is often scratched or colliding with something but it is strong and unaffected, like my brother. The middle one is the elder and gives support to the others, as I do with my brother and sister. The right-side boat has many pretty and bright yellow ornaments, cheerful and bright like my sister.

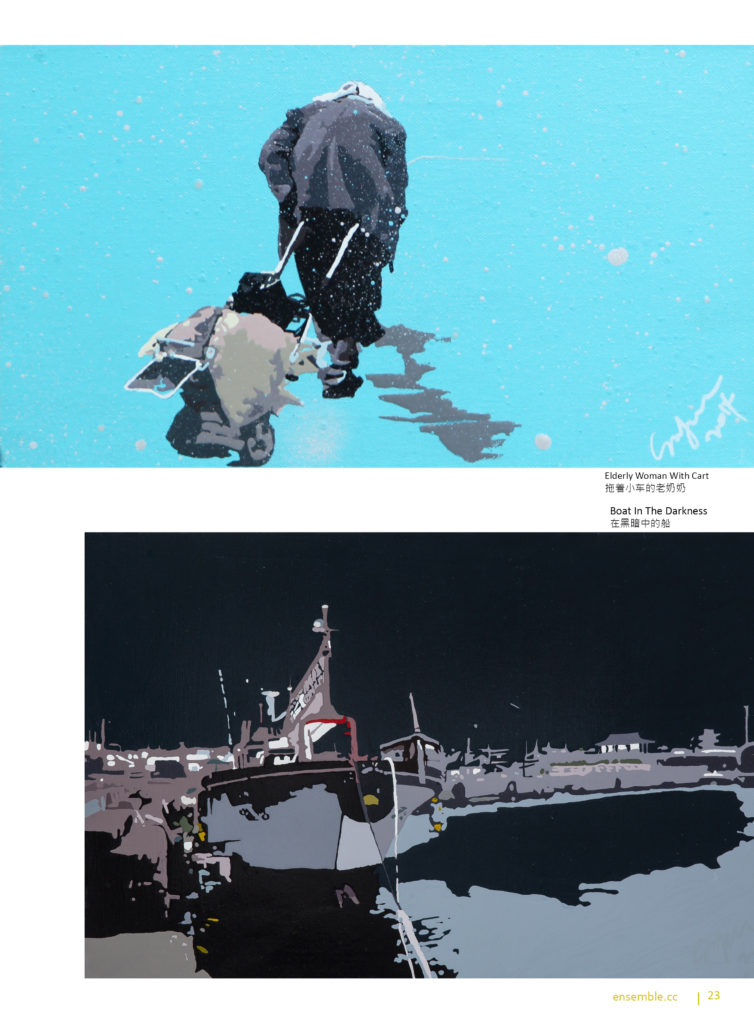

RCW: This next painting is so powerful. An elderly woman walking in a lonely landscape.

KSY: This painting is a very poignant memory for me. It was winter time. Many elderly people sustain themselves by collecting recycling materials from the trash, such as paper. There are regular days of each week for discarding paper or plastic etc. Previously, the many elderly people could collect these things and earn money to help in their simple lives. The policy for collection of trash changed and this is no longer possible. So we see many elderly people, thinner, and struggling more. When I saw this woman, she was walking with difficulty in the cold winter, behind her she pulled a little cart. In the former times, the cart would be full of recycle materials, today it is empty. The empty cart tells me how she suffers. When I saw her, I was reminded of my grandmother, who is now gone. I want to show my sympathy and care to this woman but I cannot. Despite her suffering, she continues from some kind of inner strength and resolve. I see this harsh drama of life and it deeply touches me.

RCW: You mentioned your grandparents on several occasions to me with great affection.

KSY: My grandparents’ home is small farm. On Jejudo, we have famous mandarin oranges and other wonderful products. I often spent days with my grandparents helping, watching, and learning the old ways of the old generations of Jeju. My memories are full of images of the many jars beside the kitchen door amidst the canola flowers, full of special Korean pickles and sauces made in the traditional way and preserved in clay jars. I remember my grandfather’s noisy tractor and how I rode with him on it as he worked. These memories form a thread that connects me all the way back past the generations I remember to my forebears I never met, I know them. Holding my grandfather’s hard hand and my grandmother’s soft hand, I am holding the hands that reach back generation to generation. Maybe we feel this more here on Jejudo.

RCW: This next painting is a larger ship against a dark background.

KSY: Usually I visit the harbor almost everyday. I almost always go in the daylight. I go there for inspiration and I always find a calm and quiet place in my spirit when I visit the harbor. This day, I had the impulse to drive to the harbor at night. When I arrived to see this boat, it gave me a feeling of foreboding. I like to walk to the boats and witness them closely if possible. That night, I felt a forbidding sense and photographed it from a distance. I felt a bit frightened and a bit depressed. The following day, I looked at the photograph and saw it quite differently. My fearful feeling was gone and I saw the light and image in a positive way which surprised me. The contrast of yellow and blue was very interesting. Because of the darkness, the body of the ship is concealed in places and unclear, it emerges from the dark. I found this memory let me feel the intersection of my own character. The experience, the memory, has both a dark or depressing side and at the same time there is a brightness and strength. Finally, the harbor always brings me strength in seeing myself and the bigger world. Even with both of my feet on this island, I find the world through these experiences where the ocean meets my shore.

RCW: How long has your family lived on Jejudo?

KSY: Our family register goes back 25 generations on Jejudo. Over 300 years.

RCW: In the future do you feel that you will remain here or do you plan to move away from Jeju Island?

KSY: I have traveled and lived abroad in the past. When I arrived in the big cities, I was so excited and impressed by the energy, the tall buildings, the many people, but after a while I find it overwhelming and unpleasant. I find myself called to return to my homeland, my harbors, mountains, and family.

Be the first to comment